The eternal sunshine of the capitalist mind

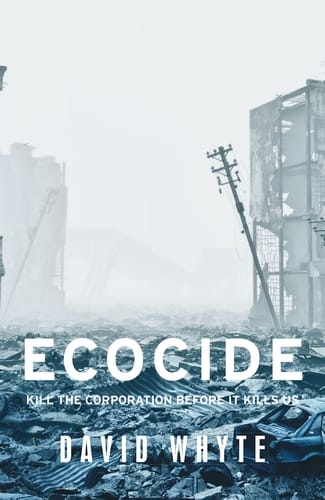

Here I republish a slightly edited book review I did of David Whyte's Ecocide.

There is a book called The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind that I have never read. It was made into a film, and that I have seen. If you have never seen the film I am about to spoil at least some of it for you, sorry. As with most stories involving people the protagonists meet and fall in love, but their relationship is marred with painful jealousy. One of them gets a new medical treatment that removes all memory of the other and it causes a lot of pain and confusion. Each gets their memories removed several times over the course of the film, but they always seem to find each other and so it happens again.

The thesis is, to some degree anyway, sometimes you would be happy if you could remove painful memories and just not experience the pain they bring any more. You could find some kind of eternal sunshine, some happiness, even bliss, if you could have no memory of the things that cause you pain. This is related to the Buddhist idea of nirvana, where the fires of wanting, of passion are blown out, and things are just things without all the pain of having and needing. Except, I imagine, an enlightened person would still remember things without the resonance.

Why start with this idea?

In another piece I have written recently, Empire Socialism, I talk about cognitive dissonance, and The Spectacle. Here there is something that is even more pernicious. There are things that very rarely even get discussed. The true elephant in the room for capitalist society is the ecocide that’s coming, ready or not, and may well take us all with it. The engine of this destruction is the corporation. Corporations are everywhere, they are killing us, and yet never mentioned in most mainstream media.

In discussions with people online and other places you often find a really strange love for capitalism, and also the state. The fundamental, undeniable fact, you can’t have infinite growth in a finite system just doesn’t seem to register in their minds. They often list a whole host of platitudes about how it has lifted people out of poverty, and all sorts of beneficial things for humanity. The flip side of 300 years of slavery, murder, theft, and planetary rapine in general is curiously absent, even excused by some as part of Capital’s civilising influence. There’s also the usual arguments about not going against human nature, which has been debunked so many times by socialists (and others) that it doesn’t really bear thinking about any more.

This glowing love for capitalism is quite creepy. It feels like how one might interact with a victim of abuse or cult member, no amount of trying to point out the single fact that makes it dangerous and untenable works. Just as with conspiracy theorists, there’s always a new excuse, a new whuddabout, a new specious comparison, a new false equivalence that explains inequality, that means the starry-eyed look continues and things don’t need to change fundamentally. The theory is continually stretched to meet the reality, rather than the reality causing the abandoning of the theory.

In its own way it’s really quite bizarre, it’s the new religion that we can’t avoid being taken in by. After all, the shiny things we think we need are part of the price we pay for entry to the Spectacle.

The corporation

Finally we get to the meat of this article, which is a review and commentary on David Whyte’s timely and chastening book Ecocide – kill the corporation before it kills us. I remember his earlier work, such as How corrupt is Britain? and co-author of The Violence of Austerity so I was keen to read this latest one. I confess I couldn’t finish Violence, not because it’s a bad book, far from it, but it’s very harrowing to read.

The concept of Ecocide came out of the work of international lawyer Peter Falk after the destruction caused by Agent Orange (another wonderful Monsanto product) in the Vietnamese war that caused enormous and continuing environmental damage and loss of life, and the Bhopal disaster in India, where a gas leak from a chemical plant killed and damaged thousands with zero consequences for the polluters. The concept exists, but the law has never been ratified.

The book opens with a short history of the corporation. The earliest example on record, a corporation now called Stora Enso, is also one that is still around. It is also associated with one of the earliest eco disasters recorded, permanent damage of the water courses and land around a copper mine in an area that is now an international heritage site. This is not an accident. One of the other phenomena he notes is that the corporation is never discussed in the media or wider society. This particular corporation, hundreds of years later, now one of the biggest paper manufacturers in the world, is still causing damage.

You may have seen the meme that says nearly all of the greenhouse gas produced is done so by less than 100 corporations. We know this, but we don’t know who they are, and even if we did they are well protected and doing nothing illegal.

Corporations are useful for the capitalist class. The concept of limited liability meant that risks could be taken without risking all of your capital. Any financial risk or punishment for wrongdoing or incompetence stopped at the assets held by the company and at the doors of the company itself. This is also used, for example, where companies doing something stupid or risky like fracking lease or borrow their equipment and assets. They are also usually subsidiaries of larger capitalist interests, which allows them to limit any losses to the smaller company. This means that, if they are sued, it costs their ultimate owners nothing.

Corporations became investment vehicles, where the goal has become to increase the much vaunted shareholder value and whatever goods or services it provides has become incidental with the financialisation of the world economy. Financialisation has meant that the original nominal intention of the corporation is now absorbed into solely making money. In general CEOs care about profits before all else, and this is reflected in the way the corporation behaves, they could be fired if they behaved in any other way.

We arrive at a split where the investment, and the care and growth of the investment, are two separate things. So attempting to get corporations to behave in a moral way is pointless. The forces that drive their behaviour are solely about growth and profit, which have no morals and take no responsibility.

Examples of everything from climate change to leaded petrol always put profit first, it’s the nature of the beast. The separation of money from the things it has to do to accumulate and grow means it can’t be controlled. The creative destruction promised by thinkers like Hayek means the dehumanising mayhem is never stopped or held accountable.

This is why things happen, and keep happening, that are inimical to life surviving on this planet. The systems and processes that run our society and provide the things we need to survive do not have the eco system as a priority, no amount of hand-wringing or laws will change this. It is embedded in the way things are organised and done.

Neocolonialism

Colonialism went out of fashion after the second world war. The inexhaustible desire to steal the wealth of other countries did not. So instead corporations came up with different ways of dominating the places they needed to get their raw materials from. Whyte shares the three stage plan they use:

- They gain the support of the host state

- The support ensures that the wealth flows to the elites in control of the state and nobody else

- The corporation’s home state hosts the elites and their children, making them feel important, and also under control. The governments of the home states often invest in the corporations too.

They use the same pattern everywhere in the global South, the destruction wrought by big agriculture, the monocropping and soil destruction, the patenting of seeds used by indigenous peoples, the environmental destruction as conflict minerals are torn out of the ground, are all maintained and controlled using this neocolonial pattern.

Regulation

Regulation is imposed from above to stop capitalism eating itself. [p. 116]

The long supply chains used by modern corporations provide a perfect machine where they can avoid regulation and hide embarrassing things. It insulates the real owners from consequences. An example of this is the really destructive use of artisanal mining to get resources out of the ground. The minerals get to the corporation, but it isn’t responsible for the destruction, just for creating the environment where an expensive commodity ends up where they need it.

Government regulation in the corporation’s home country does not figure, it doesn’t care and indeed does not know about the beginnings of the chain, only the end. This is also part of nonsense like carbon trading, where the trading takes place after the carbon is out of the ground. The concept, the very idea, of keeping it in the ground doesn’t figure. The locals pay the price for the global need. This point has interesting parallels with David Jensen somewhere in part 1 of his opus Endgame who points out that once a resource has global reach the demand for it is effectively infinite and it won’t stop until there is nothing left.

As the double movement of regulation is undermined by financialised models of debt, capitalist industries become more and more difficult to regulate. [p. 117].

Home state regulation does not take into account ecocide, as stated earlier the idea hasn’t even been ratified. Even if it were, the international court at the Hague has never prosecuted anyone from Europe, mostly African leaders past their corporate sell by dates.

Even if home countries wanted to police corporations locally they can’t. Neoliberalism has gutted the regulators, in the UK there are laws specifically banning taking action against polluters if it would damage economic growth. As Whyte points out, the Environment agency employs about 1,000 people, which sounds a lot, but there are more traffic wardens in London alone. The figures spent on trying to control this are risible and shrinking in the UK and the USA, and there is no reason to think other countries are any better.

Some people get sick, some people get a pay rise. The two things are not unrelated. [p. 131]

The corporate veil

So we have a discreet veil drawn over the things corporations get up to; the disconnections and discombobulation in the supply chains mean no-one in the home country can be held responsible. Even if a company is fined it’s a business expense that can be written off against tax. For example, when BP were fined $20bn by the US government for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill they recovered nearly half of it from their tax bill. Where there is no regulation to speak of similar events happen off the coast of Nigeria quite frequently and no compensation has ever been paid.

No farce any more

Hegel’s aphorism that history repeats itself; the first time as tragedy, the second as farce has been transformed by neoliberalism to a continuous cycle of ecological tragedy. Tragedy makes profit, then more profit from the tragedy, and so on.

This is another source of eternal sunshine. The true believers are incapable of seeing how their beloved investments are cared for, they act blissfully unaware of the environmental damage and blatant trampling over people, up to and including consequence free murder. They are unaware that the people raised out of poverty had somewhere to live and enough to eat before they were driven off the land, and originally didn’t need to be raised from anything.

The regulations that control corporations do not prevent them from doing anything with bad consequences. Instead they place limits on the damage that can be done. Anti-pollution measures still permit the poisoning of the atmosphere and water, they simply say how much is allowed before a fine might be levied. The regulations are there to increase the longevity of the damage, to protect profit over the longer term, they have nothing to do with the protection of people. Fines can be treated as expenses for tax purposes, anyway.

Whyte points out that so-called deregulation beloved by Thatcher, Reagan, Clinton and others is in fact reregulation, where the limited protections that were put in place to prevent damage to the economy in better times were removed.

Another strange irony, as human rights and anti-discrimination laws were drafted and enacted in the twentieth century, was that those laws were pre-eminently applied to corporations. Corporations are treated as people with free speech and all kinds of rights that can’t be discriminated against. In fact, as detailed in White Rage, the equal rights laws that were fought for so hard in the 1960s, were applied more often to corporations than people. The US supreme court also found in favour of corporations most of the time and people far less often.

There is a very interesting section on green washing the corporation and the non-solutions that capitalists have been playing with while things get worse. For brevity, this won’t be covered here.

Conclusions

Whyte closes by pointing out we are not in control of the corporation and it’s killing us. Less than 100 corporations are responsible for 71% of the carbon emissions, rather than crying about plastic drinking straws we should be concentrating on shutting them down. He proposes a corporate death penalty:

- Corporate structure must be broken, the activities of any corporation must be limited to doing one thing, abolish cross ownership of each other to limit the damage they can do.

- Impunity for investors and share holders must end. Limited liability is unsustainable. They must be held fully responsible for any activities they profit from. Asset shielding must be ended, and equity fines implemented.

- Impunity for corporate executives must end. There is an argument that doing this would affect the pool of talent for executives who might flee to other countries that are less likely to hold them responsible if things go wrong. Who cares if this puddle is a little less deep?

Final words

Now we return to torturing the metaphor from the film. If I recall correctly the film ends with them meeting on the same beach again and expressing interest in each other, but there is also a frisson of the removed memories still there, one of the characters says:

“I will hurt you”

The other replies:

“I don’t mind”

As in this was meant to be, this technology can’t stop affairs of the heart, some things almost have to happen. So we see their love winning against a technology that keeps destroying it. This is all very sweet.

As our minds sit spotless in the eternal sunshine of the corporation we must realise that this is not what needs to happen. Instead of having our memories cleaned of capitalism’s evils we must instead get to what is actually happening and why. We are hurting and we could easily die if the corporation continues. This is not merely an affair of two lovers, it is one of survival for us all. A spotless mind that ignores the damage the corporation does will not ultimately be a place without suffering, it will simply be a place that ignores the suffering of others at great eventual cost to itself. Ignoring the coming ecocide and its causes is not the work of a spotless mind but a fool.

Let’s end with two key quotes from the end of the book:

Restoration of the common ownership of the land and of natural resources is crucial if we are to reverse climate change … the logic of capital accumulation always encourages the devouring of nature without human and ecological limits … Only through a restoration of the commons can we displace the social dominance of capital and the corporation over the future of the planet and allow the damage to our environment to be repaired.

The closing words:

… it is hardly radical to suggest that if something is killing us we should over-power it and make it stop. And this is what we need to do. We need to kill the corporation before it kills us.